Clement Attlee

Labour Party

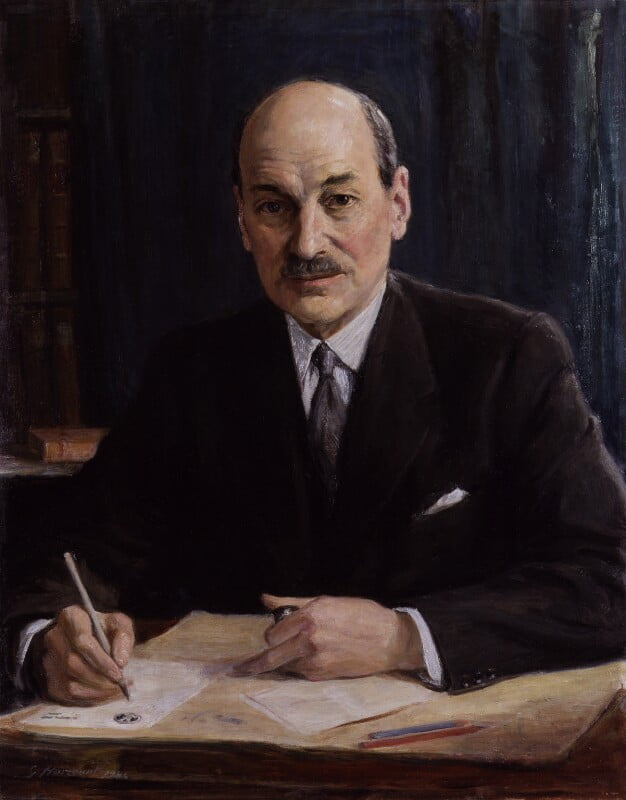

Image credit: Clement Attlee, George Harcourt, 1946. © National Portrait Gallery, London licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Clement Attlee

You will be judged by what you succeed at gentlemen, not by what you attempt

Labour Party

July 1945 - October 1951

26 Jul 1945 - 26 Oct 1951

Image credit: Clement Attlee, George Harcourt, 1946. © National Portrait Gallery, London licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Key Facts

Tenure dates

26 Jul 1945 - 26 Oct 1951

Length of tenure

6 years, 92 days

Party

Labour Party

Spouse

Violet Millar

Born

3 Jan 1883

Birth place

Putney, England

Died

8 Oct 1967 (aged 84 years)

Resting place

Westminster Abbey

About Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee was the leader who did the most to shape Britain after the Second World War. During his premiership the National Health Service was created. His government also legislated for the modern system of National Insurance, the National Parks system, and the New Towns Act. Abroad, Attlee began decolonisation, while binding the UK into NATO. Many consider him the greatest of Britain’s Prime Ministers.

Clement Attlee was born in a middle-class family in Putney. He was educated at Haileybury and University College, Oxford. He graduated in 1904, and then trained as a barrister at the Inner Temple, being called to the bar in 1906. It was at this time, whilst volunteering for the Haileybury House charity, that he became aware of the poverty in London. He became convinced that state action, rather than charity, was the only way to alleviate such deprivation. He joined the Independent Labour Party in 1908.

At this time, he worked as a secretary for socialist campaigner Beatrice Webb and was a member of the Fabian Society. In 1911, he was employed as an ‘official explainer’ for the government’s National Insurance Act.

In 1914, upon the outbreak of war, Attlee attempted to join the British army, but at age 31 he was initially turned down. Undeterred, he was eventually commissioned as a lieutenant. He served in Gallipoli, being hospitalised with dysentery. Upon his return to the frontlines, his company was the last to be withdrawn from Suvla Bay. He was the penultimate man to leave the beach on 20 December 1915. After that, Attlee served in Mesopotamia, being wounded, after which he served in England as a training officer. He finished the war with the rank of Major.

After the war, Attlee returned to London, becoming the mayor of Stepney and leading a campaign to take on slum landlords. He wrote a book at this time, setting out his philosophy of government action to alleviate deprivation.

In 1922, Attlee was elected MP for the Limehouse constituency. He assisted Ramsay MacDonald in his efforts to become Labour leader and was promoted to Under-Secretary of State for War in MacDonald’s short-lived 1924 government.

In 1927, Attlee was appointed to the Simon Commission on Indian self-rule. In this role, he familiarised himself with the issues of India and met many of the pro-independence leaders. He developed a sympathy towards Indian independence.

Though he was a part of MacDonald’s 1929-31 ministry, as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Postmaster General, he refused to follow MacDonald’s decision to create a National government with the Conservatives. A deeply divided Labour Party lost 235 seats in the subsequent election, leaving them with just 57. Attlee held onto Limehouse by just a few hundred votes. With the Party’s leadership largely ejected from Parliament, Attlee became deputy leader.

In October 1935, Labour leader George Lansbury resigned after party delegates voted in favour of sanctioning fascist Italy. Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin called a snap election, hoping to capitalise on Labour’s division. With no choice, Labour agreed that Attlee should lead. Ultimately, Labour won just over 100 seats. In the subsequent leadership election, Attlee won in the second ballot.

Initially, as Leader of the Opposition, Attlee opposed rearmament, however, as the threat of the Nazis became clearer, he changed tack. He now opposed the government’s policy of appeasement. When war finally came in 1939, Attlee remained Leader of the Opposition. In 1940, it was he who told Chamberlain that he must leave the premiership for a coalition to be formed.

Attlee then served in Churchill’s war cabinet, initially as Lord Privy Seal, and then as Deputy Prime Minister from 1942. In this position, he played a key role in the formulation of domestic policy. At the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, Attlee told Churchill that the coalition now had to end, and the election (which had been due in 1940) had to happen that summer.

On 26 July 1945, contrary to Attlee’s own expectations, Labour won a landslide election victory. What followed was one of Britain’s great reforming governments. It was this government that created the modern welfare state, including the creation of the National Health Service and the modern system of National Insurance.

Attlee’s government also nationalised both the major strategic industries and thousands of smaller businesses. Railways, road transport, airlines, energy companies, and the iron and steel industries all came under government ownership. This created the ‘mixed economy’ system that would form the basis of government economic policy until the 1970s.

Abroad, Attlee aligned Britain with the United States, and Britain was one of the founder members of NATO in 1949. India was decolonised and Britain’s mandate in the Middle East ended. It was also Attlee’s government that invested in a British nuclear weapons programme, with the first British nuclear test in 1952.

By 1950, however, the government was becoming more divided over the introduction of prescription fees in the NHS, and Britain’s commitment to the Korean War. That year, Labour’s majority was reduced to single digits. In October 1951, Britain went to the polls again, this time with the Conservatives winning a majority and Attlee leaving Number 10.

Attlee remained Labour leader until 1955, having spent two decades at the top. After that, he retired to the House of Lords, making occasional interventions into politics. He died in 1967.

Attlee had a reputation as a taciturn, modest, and unassuming individual. However, he was a decisive, effective, and occasionally ruthless, Prime Minister. Few have matched his achievements in office.

Premiership

Labour had campaigned in the 1945 election with a manifesto called Let us Face the Future. The campaign itself was focused on building a new Britain, which contrasted strongly to the Conservative campaign, which focused on Churchill. Most predicted that the Conservatives would win the election, but they were due for a surprise.

When the results of the 5 July election were announced on 26 July (with a wide gap because there were so many military ballots from the Far East) Labour had won a landslide victory, with a working majority of 146. At this point, Labour grandees reportedly considered replacing Attlee, but the plot failed and Attlee went to the Palace to see George VI.

The circumstances of the Attlee government were not good. Britain was still at war against Japan. The country was deeply indebted. Parts of British cities lay in ruins due to wartime bombing. The consumer economy had been devastated. Moreover, in Europe, the Soviet Union was increasingly emerging as a geopolitical threat that would need confronting and containing. Further afield, Britain had promised independence to India, while British rule in mandatory Palestine grew shaky. On top of all this, Attlee was deeply committed to delivering on the Labour Party’s election manifesto and of building the ‘Cradle to Grave’ welfare state that had been promised by the 1942 Beveridge report, and for which Attlee had advocated his entire life.

In August 1945, Japan surrendered after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The long-feared ground invasion, in which British forces were due to play a part, never needed to take place. On 15 August, Attlee spoke to the nation on the radio, saying that ‘the last of our enemies is laid low’.

With victory in the Far East, the government could turn its attention to delivering on its promises. Attlee’s government passed legislation creating the National Health Service, all overseen by Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan. For the first time, a publicly funded healthcare system was available providing treatment for all, free at the point of use. Millions of people received healthcare for the first time, with the NHS dental services treating 8.5 million in its first year.

Legislation was also passed over National Insurance. Those who paid into National Insurance were entitled to flat-rate pensions, sickness benefit, unemployment benefit, and funeral benefits. Other legislation included the Industrial Injuries and National Assistance Acts. Regulations were introduced improving health and safety in the workplace. Large parts of the British economy were also nationalised, including railways, road transport, energy, and industry.

Postwar economic policy had to deal with both the immense cost of servicing Britian’s debts and paying for the new welfare state. Wartime taxes remained high. Rationing continued. An Anglo-American loan was negotiated in 1945, which required the pound to be convertible to the dollar, which, when implemented, led to a currency crisis. From 1947, Chancellor Stafford Cripps instituted economic policies that would become known as ‘austerity’ and which would largely continue for the rest of Attlee’s premiership. Trade unions were persuaded to accept painful wage restraint. In 1949, there was another balance of payments crisis, forcing a devaluation of the pound. Britain did benefit from the Marshall Aid plan, improving the economy from 1948, and by 1950 the balance of payments was showing a surplus.

Attlee’s premiership also marked the beginning of the final phase of the British Empire. He had become firmly convinced that India should become independent after his experience of sitting on the Simon Commission during the 1920s (though the published report stopped short of such a recommendation). Moreover, in 1942, the ‘Cripps Mission’ had promised that India would receive self-government when the war ended. In 1945, upon the end of the war, Attlee set in train Indian independence, which took place in 1947, but only with bloody partition. Burma and Sri Lanka also became independent. Likewise, the British mandate concluded in Mandatory Palestine in 1948, leaving the situation unresolved, and war broke out after the British withdrawal between the newly declared Israel and the surrounding Arab powers.

Attlee largely left foreign policy in the hands of Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin. He helped to establish NATO, with Britain joining at the outset. It was also Attlee and Bevin who decided that there must be a British nuclear programme. In Europe, Britain stood with the US, as the Cold War began to develop. Attlee also sent British forces to fight Malaysian communist insurgents in 1948 and, much more significantly, to support the United Nations’ mission to defend South Korea from communist North Korea’s aggression in 1950.

Labour won the early 1950 election with a million more votes than in 1945, but with a majority of just 5 seats. By then, the fissures in the government were beginning to show, with divisions over Britain’s heavy commitment to the Korean War. In 1950, Attlee’s ally Stafford Cripps resigned due to ill health and the following year Ernest Bevin died. In 1951, Aneurin Bevan resigned over the introduction of NHS prescription charges due to rearmament. In the autumn of 1951, Attlee went back to the country for another election. This time, Labour was defeated, despite gaining over 200,000 more votes than Churchill’s Conservatives.

The Attlee governments reforms created the ‘Post-War Consensus’ of British politics, which was built around Keynesian economics, a mixed economy, and a large welfare state. This system prevailed until the 1970s. The permanent legacies of the Attlee government include the NHS and the provision of a ‘Cradle to Grave’ welfare state. Much of Labour’s 1945 manifesto was achieved during Attlee’s premiership. It is with good reason that many historians have rated Clement Attlee as one of the greatest of Britain’s Prime Ministers.

Personal life

Attlee married Violet Millar in 1922. It seems to have been a genuinely happy marriage and they had four children. She died in 1964, three years before Clement Attlee.

Parliament

Attlee represented the constituency of Limehouse in London’s East End for his entire political career. For most of his career he achieved a heavy majority, but in 1931 he retained the seat by just 551 votes.

In Parliament, Attlee saw the Labour Party go from being the largest party in 1928, to almost being wiped out in 1931. Once he became leader, he led the party to recovery in 1935 and to power in 1945. He remained Leader of the Opposition after leaving Number 10, even contesting the 1955 election against Anthony Eden’s Conservatives.

As Prime Minister, Attlee faced Winston Churchill across the Despatch Box, frequently besting him. In the words of historian Dick Leonard, Attlee’s ‘dry, authoritative, clipped responses regularly [punctured] the overblown rhetoric of a master platform performer’. (Dick Leonard, A History of British Prime Ministers (London, 2015) p. 647).

Key Events

Key Insights

Collections & Content

Andrew Bonar Law

Bonar Law was the shortest serving Prime Minister of the 20th Century, being in office for just 209 days. He was gravely ill when he t...

The Earl of Rosebery

Lord Rosebery was Gladstone’s successor and the most recent Prime Minister whose entire parliamentary career...

Arthur James Balfour

Arthur Balfour was Salisbury’s successor. He had a reputation as a good parliamentarian, a capable minister, and an excellent ta...

The Duke of Wellington

Wellington is a Prime Minister who is today largely remembered for achievements unrelated to his premiership. ...

The Duke of Grafton

The Duke of Grafton believed, according to Horace Walpole, that ‘the world should be postponed to a whore and a...

Benjamin Disraeli

Charming, brilliant, witty, visionary, colourful, and unconventional, Benjamin Disraeli (nicknamed ‘Dizzy’) was one of the greate...

Boris Johnson

Boris Johnson is one of the most charismatic and controversial politicians of the modern era. To supporters, he was an authentic voice wh...

The Earl Grey

Earl Grey was the great aristocratic reformer. His government passed the ‘Great Reform Act of 1832’, ending an entire e...