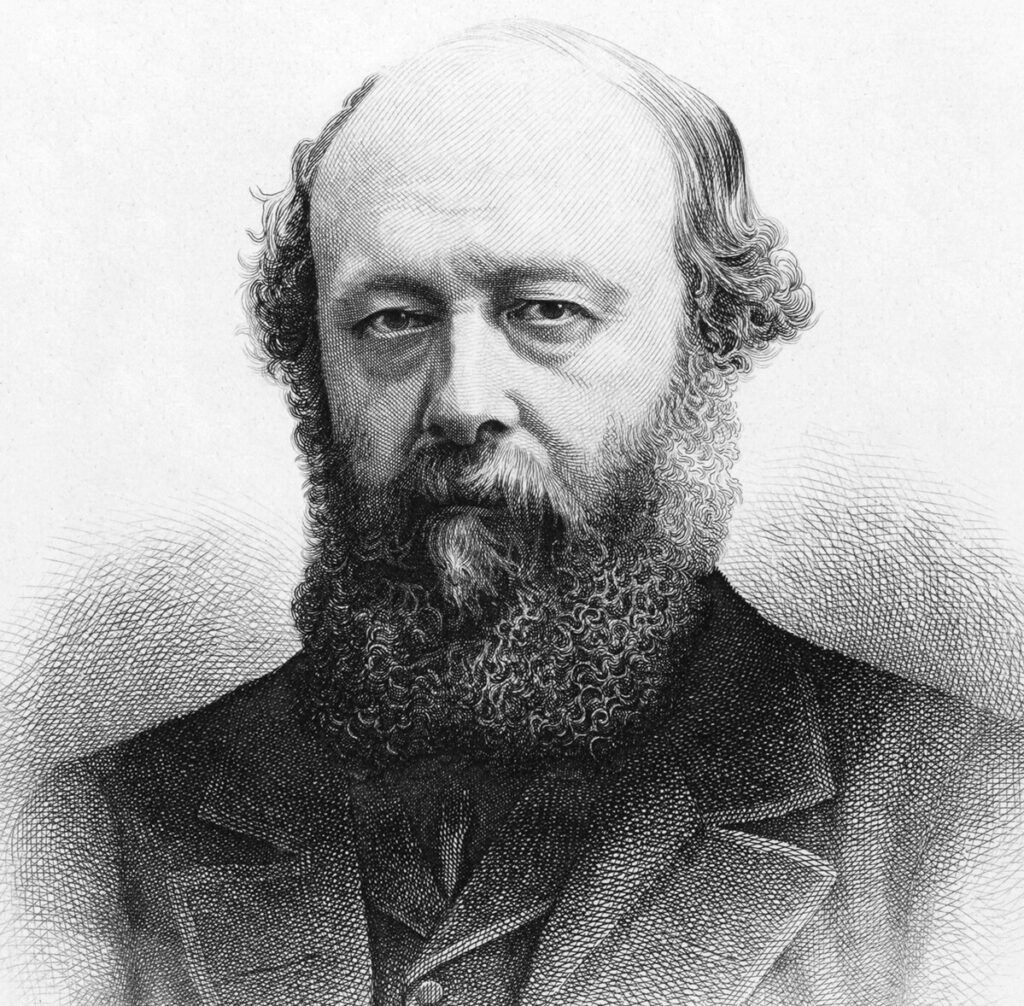

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Conservative Party

Image credit: Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, George Frederic Watts, 1882. © National Portrait Gallery, London licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

We are trustees for the British Empire. We have received that trust with all its strength, all its glory, all its traditions; and the one thing we have to care for is that we pass them untarnished to our successors.

Conservative Party

June 1885 - January 1886

23 Jun 1885 - 28 Jan 1886

|July 1886 - August 1892

|25 Jul 1886 - 11 Aug 1892

Image credit: Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, George Frederic Watts, 1882. © National Portrait Gallery, London licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Key Facts

Tenure dates

23 Jun 1885 - 28 Jan 1886

25 Jul 1886 - 11 Aug 1892

25 Jun 1895 - 11 Jul 1902

Length of tenures

13 years, 252 days

Party

Conservative Party

Spouse

Georgina Alderson

Born

3 Feb 1830

Birth place

Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England

Died

22 Aug 1903 (aged 73 years)

Resting place

St Etheldreda’s Church, Hatfield

About The Marquess of Salisbury

Lord Salisbury was likely the most conservative Prime Minister in British history and was also the Conservative Party’s longest serving Prime Minister. He was a shrewd politician who often opposed change, but reconciled himself to the expansion of the franchise and won many elections. Though historians have frequently criticised Salisbury for his disdain towards reform, it is fair to say that Salisbury was a remarkable success on his own terms. He was the last Prime Minister to serve in the House of Lords for the duration of his premiership.

Lord Salisbury was born Lord Robert Cecil, son of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury. He was the descendant of Robert Cecil, Lord Salisbury, who was Elizabeth I’s Chief Minister. He was briefly educated at Eton, where he was bullied and deeply unhappy, before returning home to be educated by a private tutor. He studied at Christ Church, Oxford, but did not finish his degree. He also tried the law to which he did not take either.

In 1853, Cecil entered the House of Commons as MP for Stamford, and he represented the seat until 1868. During those years, he wrote considerably (and often anonymously) for newspapers, usually on foreign policy, which became his area of expertise. In 1866, he became India Secretary in Lord Derby’s government.

However, in 1867 he resigned in protest at the Reform Act, which increased the franchise. He was very angry with Benjamin Disraeli for what he considered the ‘betrayal’ of introducing legislation he had previously opposed.

In 1868, upon the death of his father, he inherited the Marquessate of Salisbury, becoming Lord Salisbury. He would sit in the House of Lords for the rest of his political career.

In 1874, he wearily accepted Disraeli’s invitation to return to government as India Secretary. Salisbury dreaded working with Disraeli, and yet the two men worked well together. In 1876, Salisbury travelled to Constantinople for an international conference. Two years later, Disraeli made Salisbury Foreign Secretary, and the two travelled to Berlin for a conference to reorganise the Balkan peninsular. It was a triumph and Disraeli returned proclaiming ‘peace with honour’.

In 1881, when Disraeli died, Salisbury replaced him as Conservative Party leader (sharing the leadership with Sir Stafford Northcote). In opposition, he negotiated with Gladstone to find a compromise on the 1884 Reform Bill. Salisbury insisted on a balance between rural and city constituencies, and also on ending the two-member constituency system and replacing it with single-member constituencies. It was a masterstroke, damaging the Liberals over time, because they could no longer offer ‘balanced tickets’ reflecting both wings of the party. Meanwhile, Salisbury worsened Liberal divisions by working with the breakaway Liberal Unionists.

In 1885, he had his first, brief, premiership. But the Conservatives lost the election at the end of the year, and Gladstone returned. But the Liberals were bitterly divided over Irish Home Rule. In the July 1886 election, the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists won 393 seats, and Salisbury became Prime Minister again, this time on a much more secure footing.

Politically, Salisbury was a conservative aristocrat. His beliefs were informed by a deep sense of Christianity and also a habitual pessimism. He tended to oppose change and was afraid of revolutionary upheaval. But he was not a simple reactionary; though he opposed the 1867 Reform Bill, he learned to work with it, and his Conservative Party became a very successful electoral force. His government passed legislation providing free primary schooling and creating county councils. Though his focus was management, not reform.

Salisbury chose to also be Foreign Secretary in all three of his premierships (except for the last two years of his third). He became Prime Minister at a point when the British Empire and British power were at a high point. In foreign policy, he adopted a policy of naval strength combined with isolation, eschewing foreign alliances. During his premiership, Britain obtained a vast amount of African territory during the ‘Scramble for Africa’. He worked carefully with the European powers to ensure that the era’s land grabs did not end in war between them. In 1898, he forced France to back down during the Fashoda incident.

Salisbury also had more mundane matters to deal with, including his fiery and ambitious chancellor Lord Randolph Churchill. In December 1886, Churchill demanded defence cuts, presenting his resignation in the assumption that the Cabinet would give way. But Salisbury seized the opportunity and simply accepted Churchill’s resignation, ruining the man’s career at a stroke.

In 1892, the Conservatives narrowly lost the general election, and Gladstone returned to power. Once again, Salisbury worked to thwart Home Rule in Ireland, leaving the problem for the 20th Century. After the failures of Gladstone and Rosebery, Salisbury’s Conservatives delivered another landslide victory in 1895 and he returned to power.

During his third ministry, Salisbury relied heavily on his nephew Arthur Balfour, who was increasingly seen as his successor. He also had to deal with the powerful and assertive Liberal Unionist Joseph Chamberlain, who Salisbury appointed Colonial Secretary. Chamberlain provoked a war in South Africa (the Boer War), which initially went badly, and tarnished Salisbury’s third premiership.

Nevertheless, the war was popular, and in the ‘Khaki election’ of 1900, Salisbury won another election victory. Salisbury used the next two years to see the war to its cruel conclusion, though achieved little else. He resigned in 1902.

Salisbury married Georgina Aderson in 1857 and they had eight children. She died in 1899.

Lord Salisbury died in 1903, at Hatfield House, where he had been born, 73 years before.

Key Insights

Collections & Content

Andrew Bonar Law

Bonar Law was the shortest serving Prime Minister of the 20th Century, being in office for just 209 days. He was gravely ill when he t...

The Earl of Rosebery

Lord Rosebery was Gladstone’s successor and the most recent Prime Minister whose entire parliamentary career...

Arthur James Balfour

Arthur Balfour was Salisbury’s successor. He had a reputation as a good parliamentarian, a capable minister, and an excellent ta...

The Duke of Wellington

Wellington is a Prime Minister who is today largely remembered for achievements unrelated to his premiership. ...

The Duke of Grafton

The Duke of Grafton believed, according to Horace Walpole, that ‘the world should be postponed to a whore and a...

Benjamin Disraeli

Charming, brilliant, witty, visionary, colourful, and unconventional, Benjamin Disraeli (nicknamed ‘Dizzy’) was one of the greate...

Boris Johnson

Boris Johnson is one of the most charismatic and controversial politicians of the modern era. To supporters, he was an authentic voice wh...

The Earl Grey

Earl Grey was the great aristocratic reformer. His government passed the ‘Great Reform Act of 1832’, ending an entire e...